- Home

- Jean Merrill

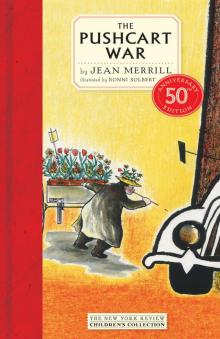

The Pushcart War

The Pushcart War Read online

The Pushcart War

By Jean Merrill

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

Ronni Solbert

THE NEW YORK REVIEW

CHILDREN’S COLLECTION

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Text copyright © 1964 by Jean Merrill; copyright © renewed 1992 by Jean Merrill

Illustrations copyright © 1964 by Ronni Solbert; copyright © renewed 1992 by Ronni Solbert

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Merrill, Jean.

The Pushcart War / by Jean Merrill; illustrated by Ronni Solbert. — 50th anniversary edition. pages cm. — (The New York Review children’s collection)

Originally published by W. R. Scott in 1964.

Summary: The outbreak of a war between truck drivers and pushcart peddlers brings the mounting problems of traffic to the attention of both the city of New York and the world.

ISBN 978-1-59017-819-5 (hardback)

[1. Trucks—Fiction. 2. Peddlers—Fiction. 3. New York (N.Y.)—Fiction. 4. War—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.M54535Pu 2014

[Fic]—dc23

2014014592

ISBN 978-1-59017-820-1

v1.0

Cover design by Louise Fili Ltd.

For a complete list of books in the NYRB Classics series, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT AND MORE INFORMATION

FOREWORD

INTRODUCTION

I. How It Began: The Daffodil Massacre

II. The Blow-up of Marvin Seeley’s Picture

III. More About Morris the Florist & A Little About Frank the Flower and Maxie Hammerman, the Pushcart King

IV. The Summer Before the War

V. Wenda Gambling Sees the Danger Signs

VI. The Peanut Butter Speech

VII. The Words That Triggered the War

VIII. The Secret Meeting & The Declaration of War

IX. The Secret Campaign Against the Pushcarts

X. The Meeting at Maxie Hammerman’s: The Pushcarts Decide to Fight

XI. The Secret Weapon

XII. The Pea Shooter Campaign—Phase 1

XIII. Maxie Hammerman’s Battle Plan & General Anna’s Hester Street Strategy

XIV. Some Theories As to the Cause of the Flat Tires: The Rotten-Rubber Theory, The Scattered Pea-Tack Theory, and The Enemy-from-Outer-Space Theory

XV. The Arrest of Frank the Flower

XVI. Big Moe’s Attack on the Police Commissioner

XVII. The Pea Shooter Campaign—Phase II

XVIII. The Retreat of the Trucks & Rumors of a Build-up on the Fashion Front

XIX. The Tacks Tax & The British Ultimatum

XX. The Pea Blockade

XXI. The Barricade at Posey’s Plant

XXII. The Raid on Maxie Hammerman’s

XXIII. The Questioning of Maxie Hammerman

XXIV. The Portlette Papers: The LEMA Master Plan & The Plot to Capture Maxie Hammerman

XXV. The Three-Against-One Gamble & The Capture of the Bulletproof Italian Car

XXVI. Maxie Hammerman’s War Chest: A Philosophy of War

XXVII. The Truck Drivers’ Manifesto

XXVIII. The Truce

XXIX. The Peace March

XXX. Mack’s Attack

XXXI. The Sneak Attack

XXXII. Frank the Flower’s Crocheted Target

XXXIII. The Turning Point: The War of Words

XXXIV. The Battle of Bleecker Street

XXXV. The Pushcart Peace Conference & The Formulation of The Flower Formula for Peace

XXXVI. The Post-War Years

FOR

Milton, Martin, Morris, Moses, the two Michaels, and other truck drivers I have known in and around Tompkins Square Park,

AND FOR

Mary, who will always blow up a picture if necessary.

FOREWORD

by Professor Lyman Cumberly of New York University, author of The Large Object Theory of History

As the author says in her introduction, it is very important to the peace of the world that we understand how wars begin. Unfortunately, most of our modern wars are too big for the average person even to begin to understand. They take place on five continents at once. (One has to study geography for twenty years just to locate the battlefields.) They involve hundreds of armies, thousands of officers, millions of soldiers, and the weapons are so complicated that even the generals do not understand how they work.

The extraordinary thing about the Pushcart War is that a child of six will grasp at once precisely how the weapons worked. The Pushcart War is the only recent war of which this can be said.

The result is that we have been having more and more wars simply because the whole procedure is so complicated that peace-loving people give up trying to understand what is going on. This account of the Pushcart War should help to remedy this distressing situation. For big wars are caused by the same sort of problems that led to the Pushcart War.

Not that the Pushcart War was a small war. However, it was confined to the streets of one city, and it lasted only four months. During those four months, of course, the fate of one of the great cities of the world hung in the balance.

The author of this book is to be commended for her zeal in tracking down much behind-the-scenes material never before published. I, myself, had never heard the amusing story of Frank the Flower’s crocheted target, or the story behind Maxie Hammerman’s capture of the bulletproof Italian car, a feat that demonstrates conclusively the brilliance of Maxie’s strategy throughout the war.

Neither, I am ashamed to say, did I ever know the meaning of the inscription under General Anna’s statue in Tompkins Square Park, although it is a park in which I spent many happy hours working on my Large Object Theory of History. (The author does not mention, I believe, that Tompkins Square Park was the battleground of another famous American war—but, of course, there are very few places left that have not been battlefields.)

I am sorry to say that I think the author may be mistaken about the number of pile driving firms in New York City at the time of the Pushcart War. She gives it as forty-three, although the Pile Drivers’ Annual for that year lists fifty-three. A minor error in an otherwise impressive effort.

New York University

December 2, 2036

INTRODUCTION

As it has been only ten years since the Pushcart War, I was surprised when one of my nephews a few months ago looked puzzled at the mention of a Mighty Mammoth. Then I realized that he had probably never seen a Mighty Mammoth. (He was only two at the time of the war and, moreover, was living in Iceland where his father had been sent on a government assignment.)

That a twelve-year-old boy might never have seen a Mighty Mammoth was understandable. What astonished me was that he had never even heard of one. But I have since discovered that there has never been a history of the Pushcart War written for young people.

Professor Lyman Cumberly’s book, The Large Object Theory of History, drawn mainly from his observations of the Pushcart War, is a brilliant work. However, it is written primarily for college students.

I have always believed that we cannot have peace in the world until all of us understand how wars start. And so I have tried to set down the main events of the Pushcart War in such a way that readers of all ages may profit from whatever lessons it offers.

Although I was living in New York at the time of the war and saw the stre

ets of New York overrun with Mighty Mammoths and Leaping Lemas, I did not then know any of the participants personally—except Buddy Wisser. I did contribute in a small way to the decisive battle described in Chapter XXXIV but, like most New Yorkers, was asleep in the early days of the war as to what was at issue—until Buddy Wisser alerted us all with his 160-by-160-foot enlargement of Marvin Seeley’s photograph of the Daffodil Massacre.

Needless to say, Buddy Wisser has been a great help to me in the writing of this book. Buddy, before he became editor of one of New York’s largest daily newspapers, had been sports editor of my high school newspaper, and at the time of the Pushcart War, Buddy and I still ran into each other occasionally at Yankee Stadium.

It is to Buddy that I am indebted for the story behind the story of Marvin Seeley’s picture. And it was through Buddy, of course, that I was able to meet many of the brave men and women who fought in the Pushcart War.

In addition to Buddy Wisser, I would like to express my appreciation to Maxie Hammerman for the many hours he spent answering my questions about his recollections of the war. Thanks, too, to Joey Kafflis for his permission to quote excerpts from his diary and to the New York Public Library’s Rare Document Division for letting me see “The Portlette Papers.”

Jean F. Merrill

Washington, Vt.

October 14, 2036

The Pushcart War

CHAPTER I

How It Began: The Daffodil Massacre

The Pushcart War started on the afternoon of March 15, 2026, when a truck ran down a pushcart belonging to a flower peddler. Daffodils were scattered all over the street. The pushcart was flattened, and the owner of the pushcart was pitched headfirst into a pickle barrel.

The owner of the cart was Morris the Florist. The driver of the truck was Mack, who at that time was employed by Mammoth Moving. Mack’s full name was Albert P. Mack, but in most accounts of the Pushcart War, he is referred to simply as Mack.

It was near the corner of Sixth Avenue and 17th Street in New York City that the trouble occurred. Mack was trying to park his truck. He had a load of piano stools to deliver, and the space in which he was hoping to park was not quite big enough.

When Mack saw that he could not get his truck into the space by the curb, he yelled at Morris the Florist to move his pushcart. Morris’ cart was parked just ahead of Mack.

Morris had been parked in this spot for half an hour, and he was doing a good business. So he paid no attention to Mack.

Mack pounded on his horn.

Morris looked up then. “Why should I move?” Morris asked. “I’m in business here.”

Maybe if Mack had spoken courteously to Morris, Morris would have tried to push his cart forward a few feet. But Morris did not like being yelled at. He was a proud man. Besides, he had a customer.

So when Mack yelled again, “Move!” Morris merely shrugged.

“Move yourself,” he said, and went on talking with his customer.

“Look, I got to unload ninety dozen piano stools before five o’clock,” Mack said.

“I got to sell two dozen bunches of daffodils,” Morris replied. “Tomorrow they won’t be so fresh.”

“In about two minutes they won’t be so fresh,” Mack said.

As several students of history have pointed out, Mack could have simply nudged Morris’ cart a bit with the fender of his truck. The truck was so much bigger than the pushcart that the slightest push would have rolled it forward. Not that Morris would have liked being pushed. Still, that was what truck drivers generally did when smaller vehicles were in their way.

But Mack was annoyed. Like most truck drivers of the time, he was used to having his own way. Mammoth Moving was one of the biggest trucking firms in the city, and Mack did not like a pushcart peddler arguing with him.

When Mack saw that Morris was not going to move, he backed up his truck. Morris heard him gunning his engine, but did not look around. He supposed Mack was going to drive on down the block. But instead of that, Mack drove straight into the back of Morris’ pushcart. Daffodils were flung for a hundred feet and Morris himself, as we have said, was knocked into a pickle barrel. This was the event that we now know as the Daffodil Massacre.

These facts about the Daffodil Massacre are known because a boy, who had just been given a camera for his birthday, happened to be standing by the pickle barrel. His name was Marvin Seeley.

CHAPTER II

The Blow-up of Marvin Seeley’s Picture

Marvin Seeley had been trying, on the afternoon of March 15th, to take a picture of a pickle barrel which stood in front of a grocery store on 17th Street. Marvin had been annoyed to have a man go flying into the barrel at the very instant he snapped the picture. However, when the picture was developed, the daffodils came out so nicely that Marvin sent the picture to a magazine that was having a contest.

Although the magazine preferred pictures of plain pickle barrels to pictures of accidents, the picture won an Honorable Mention and was printed in the magazine where a newspaper editor’s wife, named Emily Wisser, happened to see it. Emily, who was fond of flowers, cut out the picture for a scrapbook she kept.

Later, when everyone began arguing about how the Pushcart War had started, Emily remembered Marvin Seeley’s picture and showed it to her husband. Emily’s husband, Buddy Wisser, had always laughed at his wife’s scrapbooks, but for once he was very interested. As editor of one of the city’s largest papers, he could not afford to laugh off a good story.

From Marvin Seeley’s picture, Buddy Wisser was able to track down a good many facts. For one thing, he was able to identify the owner of the pushcart as Morris the Florist (although you cannot see Morris’ face in the picture, as his head is well down in the pickle barrel).

Mack’s face, however, is clearly visible, as is the name of the trucking company. Mack is leaning from his cab window and scowling, and MAMMOTH MOVING is printed in large letters on the side of the truck.

Mammoth was a well-known trucking firm. The firm owned seventy-two trucks at the time. Its slogan was: “If It Is a Big Job, Why Not Make It a MAMMOTH Job?”

Mammoth trucks came in three sizes. There were the Number One’s, or “Baby Mammoths,” as the drivers called them. There were the Number Two’s, or “Mama Mammoths,” and there were the Number Three’s, the “Mighty Mammoths.” It was a Mighty Mammoth that ran down Morris the Florist.

There was a lot of argument about the size of Mack’s truck until Buddy Wisser decided to have Marvin Seeley’s picture enlarged. Buddy Wisser had the picture blown up until Mack’s face was life-size, and when Mack’s face was life-size, the pickle barrel and the daffodils and the truck were all life-size, too. Then all Buddy Wisser had to do was to take a tape measure and measure the truck.

Not that this was easy. The enlarged picture was so large that Buddy Wisser had to go to a park near his office and lay the picture on the ground in order to measure the truck. It was a Mighty Mammoth, all right.

It was this big picture that also gave Buddy Wisser the clue he needed to identify the owner of the pushcart. In the lower left-hand corner of the picture, Buddy observed several splintered bits of the pushcart. On one of these fragments, he made out the letters “ORRIS,” and on another—“ORIST.”

Buddy Wisser’s enlargement of Marvin Seeley’s picture now hangs in the Museum of the City of New York. The Museum preserved the picture, partly because its size makes it a curiosity, and partly because it is a historical document. It is the best proof we have of how the Pushcart War actually began.

CHAPTER III

More About Morris the Florist & A Little About Frank the Flower and Maxie Hammerman, the Pushcart King

At the time of the Pushcart War, Morris the Florist had been in the flower line for forty-three years. He was a soft-spoken man, and his only claim to fame before the war was that it was impossible to buy a dozen flowers from him.

If a customer asked Morris for a dozen tulips—or daffodils or mixed snapdragons�

�Morris always wrapped up thirteen flowers. The one extra was at no cost. “So it shouldn’t be a small dozen,” Morris said.

Morris sold his flowers from a pushcart which he pushed between Sixth and Seventh Avenues from 14th Street to 23rd Street. He never went above 23rd. It was not that he didn’t like it farther uptown, but above 23rd was Frank the Flower’s territory.

Frank the Flower and Morris the Florist were not close friends before the Pushcart War, but they respected each other. Frank was the first to chip in to help buy Morris a new pushcart after Mack ran him down.

Anyone who knew Morris in those days found it hard to imagine him provoking a war. It would be closer to the truth to say that for a long time there had been trouble coming, and that Morris the Florist just happened to be standing on the corner of Sixth Avenue and 17th Street the afternoon it came.

For a long time New York had been one of the largest cities in the world. New Yorkers had long been proud that their streets were busier and noisier and more crowded than anyone else’s.

Visitors to New York would say, “It’s nice, but it’s so crowded.”

To which New Yorkers would reply cheerfully, “Yes, it’s about the most crowded city in the world.” And the city had kept on growing.

Every year there were more automobiles. More taxis. More buses. More trucks. Especially more trucks. By the summer of the Pushcart War, there were more trucks in New York than anyplace in the world.

There were also some five hundred pushcarts, though few people had any idea that there were more than a hundred or so. Probably only Maxie Hammerman really knew how many pushcarts there were.

Maxie knew, because Maxie or Maxie’s father or Maxie’s grandfather had built most of the pushcarts in New York Maxie had a shop where he built and repaired pushcarts. It was the same shop in which his father and grandfather had started building pushcarts.

The Pushcart War

The Pushcart War